President-elect Joe Biden has said he will start tackling the pandemic on Day One by issuing a federal mask mandate and rejoining the World Health Organization. He’s even expected to announce a coronavirus task force next week, months before his inauguration, according to reports.

But despite his pledge to get the pandemic under control, there’s one key lever the Biden won’t be able to pull: A vaccine mandate.

The US president has never been able to impose a federal mandate of vaccines across the country, and that won’t change anytime soon. “It goes back to the fact that the federal government is one of limited power,” says Dorit Reiss, a professor specializing in healthcare law at the University of California Hastings College of the Law.

First, presidents don’t create laws; Congress does. The president signs bills into law (or vetoes them) after the House of Representatives and Senate go through a lengthy back and forth. The president could issue an executive order that covers people who work for or with government agencies, but Congress would still be able to write up another bill to supersede it. Of course, the president could also veto that bill—but the whole scenario is highly unlikely.

Largely, matters of public health fall onto states’ shoulders. The tenth amendment of the constitution says that any law the constitution doesn’t cover goes to the states—and “the constitution doesn’t mention the words ‘public health,’” Reiss says.

What it does mention are things like collecting taxes, declaring war, and regulating interstate business. If the federal government really wanted to find a way to enforce vaccines, it could look for a way to do so by exercising one of those powers. Congress could pass laws to limit disease spread across state borders, like requiring that all Amtrak passengers be vaccinated, says Reiss. But the US Supreme Court might not let such a law stand, if the justices determined that Congress was overreaching.

States, on the other hand, can mandate vaccines. In the 1905 case Jacobson vs. Massachusetts, the Supreme Court ruled that states have the power to enforce vaccinations when they’re “necessary for the public health or the public safety.” Back then, the country was worried about smallpox; today, the precedent could let state governors mandate a Covid-19 vaccine.

Not that they’ll use that power, necessarily. For one thing, states can only mandate vaccines that have been recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), part of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ACIP would have to recommend the vaccine for all adults and children based on ample evidence that it is safe and effective, beyond the FDA’s approval or emergency authorization of a Covid-19 vaccine.

And even with ACIP’s blessing, there’s still a lot of debate about what’s “necessary” for public health, per the language in the Jacobson ruling. For example, even though Gretchen Whitmer, the current governor of Michigan, mandated masks and limited gatherings in executive orders as the state saw spikes in Covid-19 cases, the state’s supreme court overthrew that order. Currently, the Michigan Department of Health is trying to uphold these mandates instead.

This is likely why states don’t mandate vaccines across the board; instead they require that certain populations get them. Childhood vaccines, for example, are required to attend school (they do allow various exceptions, however, depending on the state). Parents who don’t want to vaccinate their children often have to homeschool them instead.

It’s not clear whether states would deploy the same strategy for Covid-19 vaccine requirements. There’s just not enough history to go on. “We’ve never had a universal adult mandate in the US,” says Reiss, even at the state level.

So how might the federal government legally get states to require the Covid-19 vaccine? Two words: ample incentives.

“I think that the path of least resistance would be for the federal government to establish guidelines for the states,” says Margaret Riley, a professor of law at the University of Virginia. Although the federal government wouldn’t force states to enforce vaccination, it could dangle a nice carrot, like it did in 1984 by holding federal highway funding over states’ heads if they didn’t raise the drinking age to 21. (It still took four years for every state to get around to it.)

Once a Covid-19 vaccine becomes widely available, however, the commander in chief will probably have to consider all the options on the table to increase confidence in vaccine adherence. When asked during the last presidential debate what he would do to encourage vaccines, Joe Biden said he’d ensure that all the data behind the approved vaccines would be completely transparent to help people make their decisions.

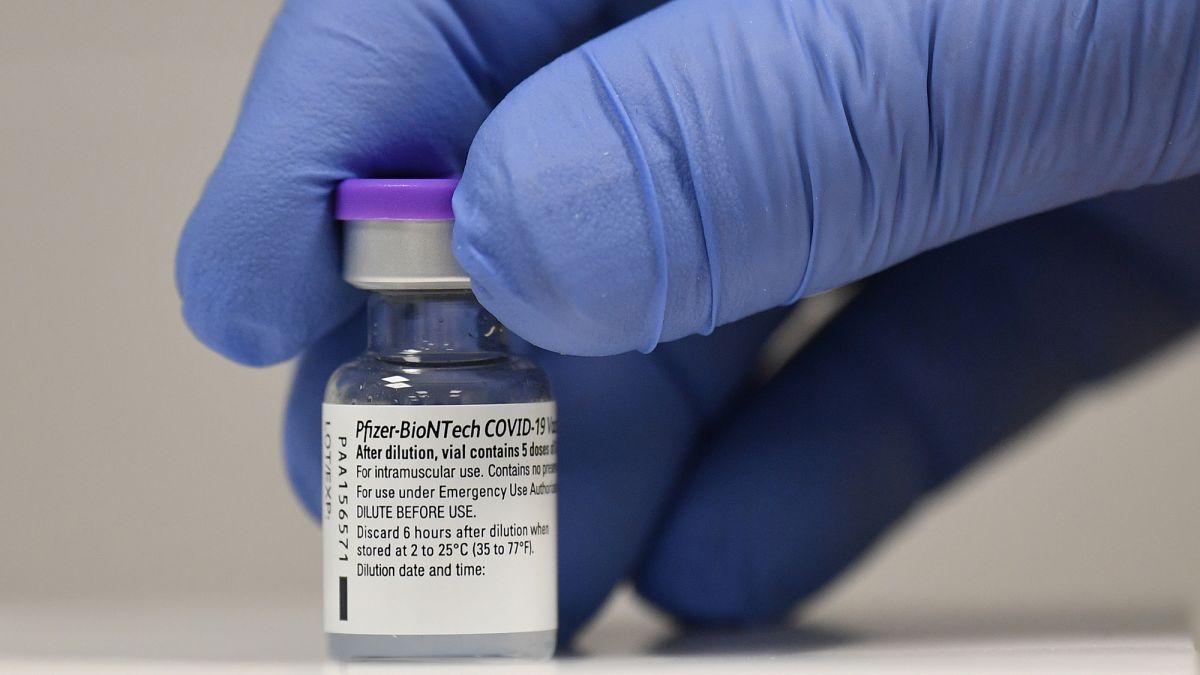

At the moment, none of the hundreds of Covid-19 vaccines in the research pipeline are ready for primetime. A handful, like those from Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Moderna, and Sinovac, are in late-stage clinical trials that could wrap up within the next few months. Vaccines will undoubtedly play a role in the way that the pandemic comes to an end, but they’ll only work if they reach everyone who needs them.